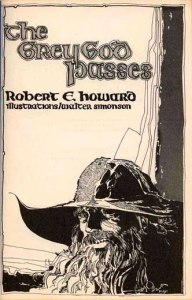

Today's story: "The Grey God Passes"

by Robert E. Howard. I came across this because Walter Simonson did the

illustrations. Simonson is most famous for his run as writer and artist

of the Thor comic in the 80s (issues 337 to 382). Howard is most famous

for Conan, of course.

Simonson

did black and white illustrations for this story back in 1975, and they

appeared in a pamphlet-style printing. Howard's story recounts the 1014

Battle of Clontarf in Ireland, which he fashions into a fight between

Christians and heathens. He's reworking history a bit with that one.

It's the story of Conn, who escapes slavery in the Orkneys and returns

to Ireland in time to aid his king in the battle. He's on the Christian

side. The grey god of the title is Odin. The story originally appeared

in a collection called Dark Mind, Dark Heart, edited by August Derleth, which contains stories by

many other writers such as Ramsey Campbell and Lovecraft.

"Grey

God" is a bit of a slog to read, which might explain why it wasn't

published in Howard's lifetime. The names, more than anything else,

weigh the story down. Just too many of them, with all the kings and

jarls and whatnot. It's still a good story, though. It was also adapted

as a comic back when Marvel was doing Conan stories (the splash page

informs us that the story has been "freely adapted" from the original;

Conan's in it).

I was hoping for a little more mythological

content. Odin is more or less an observer, seen a couple of times. First

by Conn, inciting him to return home for the battle. Then again toward

the end. He doesn't do much. There are a few fantastical elements, but

mostly it's the story of the build-up and the battle. Yeah, I really

don't have much to say about it.

I do like the art, though.

All-Star

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

Monday, February 27, 2017

A Peasant Sells a Cow as a Goat

We go back to Germany for today's story, from Ranke's collection Folktales of Germany.

In it, a poor-sighted man goes to a market to sell his goat. Three

merchants see him, knowing that he's myopic, they trick him into

thinking he has brought a goat. He sells it cheap. When he gets home,

his wife is angry at him for being duped. So he goes back to the market

with a plan. He buys himself a white hat and goes into an inn, where he

knows the bartender. He asks the bartender to play along with his

scheme. He then brings the merchants in to celebrate his success at the

market, offering them free drinks.

They sit down and drink their fill. The man then says, "Watch this," and he turns his hat in a strange manner. He then asks the bartender if the drinks have been paid for. The merchants are shocked when the bartender says yes. The merchants offer to buy the hat from him, for a small fortune. He sells it and heads home to show his wife their new wealth.

If the story ended here, it probably wouldn't be worth mentioning. But it continues:

The merchants soon realize they've been had, and they go to the nearsighted peasant's house. The wife emerges from the house before they enter, ready with the peasant's hopeful ruse--telling the merchants that the peasant is dead.

On a related note, I saw the actor John Mattey, who played one of the two leads in that movie, on tv the other day, in a commercial for Disney World, maybe? I wasn't paying attention. I was happily surprised to see that guy, who once uttered the phrase "He made it better, we'll make it more better," on the screen.

They sit down and drink their fill. The man then says, "Watch this," and he turns his hat in a strange manner. He then asks the bartender if the drinks have been paid for. The merchants are shocked when the bartender says yes. The merchants offer to buy the hat from him, for a small fortune. He sells it and heads home to show his wife their new wealth.

If the story ended here, it probably wouldn't be worth mentioning. But it continues:

The merchants soon realize they've been had, and they go to the nearsighted peasant's house. The wife emerges from the house before they enter, ready with the peasant's hopeful ruse--telling the merchants that the peasant is dead.

The wife did as she was told. But her wailing and lamenting made no impression on them. "Then we shall punish your husband after his death for what he has done to us," they told the woman and they entered the room. The peasant was lying on the floor. but this did not keep them back. They beat him so hard that the poor peasant could do nothing else but run away and hide.Now that's a good ending. I think it's truly wonderful that the merchants are satisfied not with getting their money back, but with the fact that they beat a man so hard he returned from the dead. I can't help but think that they traveled around the countryside for a day or two, trying this at any grief stricken house to which they came.

The duped merchants had taken revenge. Satisfied, they went away, because you do not succeed every day in raising a person from the dead.

On a related note, I saw the actor John Mattey, who played one of the two leads in that movie, on tv the other day, in a commercial for Disney World, maybe? I wasn't paying attention. I was happily surprised to see that guy, who once uttered the phrase "He made it better, we'll make it more better," on the screen.

Friday, February 24, 2017

Time Travel

I haven't had much success as a writer. A couple of short stories and

essays escaped into the world of publication, and a few academic

articles, mostly on mythology. One time I added up the amount of money I

have made from all that, and it came to something like four hundred

bucks (slightly more since I just got a royalty check from the folks who published my dissertation, of all things). The best thing I've written is probably a movie script called Own Worst Enemy, which I worked on with my college buddy Mike Judd. After we got a good draft done, Mike and his wife Jessica produced the film out in California. It turned out pretty good, I think.

I'm thinking about it because of the story called "All You Zombies," by Robert Heinlein, originally published in 1959. You can get a digital copy from Amazon for a few quarters. I guess it's somehow related to a recent movie called Predestination.

Now, one reason I wanted to write a move about time travel was because I didn't much like that kind of story. Wells's Time Machine wasn't very interesting until the main character gets stuck way in the future. Stanislaw Lem wrote some pretty good time travel stories, but I've never felt compelled to go back to them. The problem I find with time travel is that too many of the stories get stuck in making everything work out nice and neat, a trap that even Heinlein falls into with "All You Zombies."

However, because it's Heinlein we're talking about here, "Zombies" ends on a pretty chilling and brilliant note. I like this story a lot, despite my general antipathy toward time travel stories, and I don't want to give a lot away here. It's a story worth reading with as little foreknowledge as possible.

So when it came time to write my own time travel story, I wanted to completely obliterate the idea of the time travel paradox that fuels most of the stories. I didn't want characters to have to leave the past the same, or to have to alter the past to make things work out alright. Mike had suggested that we have the inventor mess up his own life through the use of his invention. I ran with that notion, in essence making the protagonists also the antagonists. To me, the most interesting thing about time travel is the chance to see your younger self and learn firsthand--not through nostalgia or reminiscence--the various ways you've changed over the years. I sent the characters back seven years into the past because I remembered hearing the dubious fact that every seven years all the cells in our bodies have been replaced. So if you go seven years into the past you encounter yourself as an entirely different person, in terms of biomass. I know that's got to be bunk, but it's also the stuff of inspiration.

What I'm getting at is that there's good time travel stuff out there. I liked Heinlein's The Door into Summer, too. And there's Harlan Ellison's "City on the Edge of Forever," which was an episode of Star Trek, then a script in book form, and now a comic book. I like this one because it gets rid of the inevitability that plagues many time travel stories, avoiding the idea that things have to work out the way they have already worked out. And surprisingly, some recent Transformers comics (More than Meets the Eye volume 7) really knocked the idea out of the park. The best time travel stories make their protagonists choose between equally difficult paths. There's always another angle to take on the conventions of the genre--not just deconstruction, either. I wouldn't consider Own Worst Enemy to be a deconstruction of the time travel story. It's just one of the many possibilities.

I'm thinking about it because of the story called "All You Zombies," by Robert Heinlein, originally published in 1959. You can get a digital copy from Amazon for a few quarters. I guess it's somehow related to a recent movie called Predestination.

Now, one reason I wanted to write a move about time travel was because I didn't much like that kind of story. Wells's Time Machine wasn't very interesting until the main character gets stuck way in the future. Stanislaw Lem wrote some pretty good time travel stories, but I've never felt compelled to go back to them. The problem I find with time travel is that too many of the stories get stuck in making everything work out nice and neat, a trap that even Heinlein falls into with "All You Zombies."

However, because it's Heinlein we're talking about here, "Zombies" ends on a pretty chilling and brilliant note. I like this story a lot, despite my general antipathy toward time travel stories, and I don't want to give a lot away here. It's a story worth reading with as little foreknowledge as possible.

So when it came time to write my own time travel story, I wanted to completely obliterate the idea of the time travel paradox that fuels most of the stories. I didn't want characters to have to leave the past the same, or to have to alter the past to make things work out alright. Mike had suggested that we have the inventor mess up his own life through the use of his invention. I ran with that notion, in essence making the protagonists also the antagonists. To me, the most interesting thing about time travel is the chance to see your younger self and learn firsthand--not through nostalgia or reminiscence--the various ways you've changed over the years. I sent the characters back seven years into the past because I remembered hearing the dubious fact that every seven years all the cells in our bodies have been replaced. So if you go seven years into the past you encounter yourself as an entirely different person, in terms of biomass. I know that's got to be bunk, but it's also the stuff of inspiration.

What I'm getting at is that there's good time travel stuff out there. I liked Heinlein's The Door into Summer, too. And there's Harlan Ellison's "City on the Edge of Forever," which was an episode of Star Trek, then a script in book form, and now a comic book. I like this one because it gets rid of the inevitability that plagues many time travel stories, avoiding the idea that things have to work out the way they have already worked out. And surprisingly, some recent Transformers comics (More than Meets the Eye volume 7) really knocked the idea out of the park. The best time travel stories make their protagonists choose between equally difficult paths. There's always another angle to take on the conventions of the genre--not just deconstruction, either. I wouldn't consider Own Worst Enemy to be a deconstruction of the time travel story. It's just one of the many possibilities.

Thursday, February 23, 2017

Black Bess

I find that I'm most likely to read history books of the debunking

kind. The books that tell us "the real story," or the story behind the

story. I like the tension between the official account and the allegedly

true one, the debunked version, the one that digs deeper. So I couldn't

resist a book called Lies Across America, by James W. Loewen.

It's not the kind of book that benefits from a straight read-through.

It's organized by region, and within each region by state. The book

focuses on historic sites--landmarks and statues and whatnot--telling us

what the sites themselves got wrong, often deliberately wrong. There's

tragedy behind these stories, quite often, but there's also comedy. You

can imagine how delighted I was to find, starting on page 150, this

story about Lexington, Kentucky:

There's a statue in front of the courthouse of Confederate General John H. Morgan sitting atop a stallion. Morgan wasn't a terribly significant officer--Loewen reveals that Morgan succeeded in little more than getting his men captured before getting himself shot--but his monument is significant because the "stallion" is named Bess. Apparently it's fairly common for people making monuments to soldiers to turn their mares into stallions. University of Kentucky students seem to enjoy painting the mare's testicles blue and white.

It gets better: An anonymous bard has composed "The Ballad of Black Bess." Loewen gives us a few stanzas...

Loewen wrote another book that gets to the truth obscured by official histories, Lies My Teacher Told Me. It's good stuff. Of course, there's also the work of Howard Zinn--notably, A People's History of the United States, but I think the more manageable Declarations of Independence is even better. There's Ray Raphael's Founding Myths, which specifically focuses on the American Revolution.

There's a statue in front of the courthouse of Confederate General John H. Morgan sitting atop a stallion. Morgan wasn't a terribly significant officer--Loewen reveals that Morgan succeeded in little more than getting his men captured before getting himself shot--but his monument is significant because the "stallion" is named Bess. Apparently it's fairly common for people making monuments to soldiers to turn their mares into stallions. University of Kentucky students seem to enjoy painting the mare's testicles blue and white.

It gets better: An anonymous bard has composed "The Ballad of Black Bess." Loewen gives us a few stanzas...

Proud the eye of good Black BessInteresting spelling. I've not been able to find a full version of this ballad online, though there may be a book that contains it. I'll keep digging.

With shamelessness uncanny,

She just ignores the testicules

That hang beneath her fanny.

Loewen wrote another book that gets to the truth obscured by official histories, Lies My Teacher Told Me. It's good stuff. Of course, there's also the work of Howard Zinn--notably, A People's History of the United States, but I think the more manageable Declarations of Independence is even better. There's Ray Raphael's Founding Myths, which specifically focuses on the American Revolution.

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

Unpublished Stories

I love Shirley Jackson's writing. I prefer the short stories, but her novels are great, too. Just go read Life Among the Savages if you can, to see what I mean. Yeah, The Haunting of Hill House is worth it, too (I especially love the way she blends fairy tale fantasy with horror), but I keep coming back to the short pieces.

So I got this selection of short stories called Just an Ordinary Day from the library, partly because I hadn't read "One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts" in a while. I was surprised to learn that the bulk of the collection was unpublished work, selected by her children and released in 1995--thirty years after she died.

I couldn't help thinking of Kafka, telling his buddy to burn all his unpublished work if he died. Not in a bad way, of course. Kafka's buddy Max Brod didn't burn the stuff, and so we've got a lot of stories we otherwise wouldn't have had (and apparently there are more to come, maybe). Some writers are against this sort of thing, some probably hope it works out, since the income can benefit loved ones. I'm not sure where I stand, not having much published.

Anyway, I bring all that up because I read the previously-unpublished "The Story We Used to Tell" from that collection, and it's really great. Rough, though there are no notes indicating what sort of shape the manuscript itself was in, or if Jackson left any notes about it. It's sort of a haunted house story, and I'm glad I read it even if it wasn't published in her lifetime.

I see that a biography came out last year. I might have to get a copy. "Miss Jackson writes not with a pen but a broomstick." Yeah. Sounds interesting.

So I got this selection of short stories called Just an Ordinary Day from the library, partly because I hadn't read "One Ordinary Day, with Peanuts" in a while. I was surprised to learn that the bulk of the collection was unpublished work, selected by her children and released in 1995--thirty years after she died.

I couldn't help thinking of Kafka, telling his buddy to burn all his unpublished work if he died. Not in a bad way, of course. Kafka's buddy Max Brod didn't burn the stuff, and so we've got a lot of stories we otherwise wouldn't have had (and apparently there are more to come, maybe). Some writers are against this sort of thing, some probably hope it works out, since the income can benefit loved ones. I'm not sure where I stand, not having much published.

Anyway, I bring all that up because I read the previously-unpublished "The Story We Used to Tell" from that collection, and it's really great. Rough, though there are no notes indicating what sort of shape the manuscript itself was in, or if Jackson left any notes about it. It's sort of a haunted house story, and I'm glad I read it even if it wasn't published in her lifetime.

I see that a biography came out last year. I might have to get a copy. "Miss Jackson writes not with a pen but a broomstick." Yeah. Sounds interesting.

Friday, February 17, 2017

Perfection: Muppets

Because I tend to be overly critical of things, I've been trying to

find things that I love, things that are truly great, that succeed

spectacularly in whatever they attempt to be. So every now and then I'll

be writing about these little bits of perfection. I especially try to

find them in things that are otherwise utterly without redemption. There

are lots of movies that really weren't worth the time I spent watching

them, except for a single line of dialogue, or a well-composed shot. But even stories or shows that are excellent have moments in which they transcend all expectations. I'll go through some of those every once in a while. I'm

going to start with this one sketch from The Muppet Show:

To me, that sketch is always funny. I got The Muppet Show Cast Album for my kids, which includes an audio-only version of that sketch. I've listened to it dozens of times. Always funny, for me, at least.

I must admit that I was surprised to learn, from the recent Jim Henson biography by Brian Jay Jones, that this sketch was written by Jerry Juhl right before it was filmed. Frank Oz and Jim Henson read it through once and then did the sketch in one take. According to Juhl, as quoted by Jones, it was the moment when Fozzie really came into his own.

John Seavy over at Fraggmented wrote about the Muppets as part of his storytelling engines series of blog posts. He characterizes the show's engine as the concept that failure is funny:

Looking at the Muppets, you see a group of people united by a) their passion for entertainment and their dram of making people happy through art, and b) their lack of talent at their chosen field. The gap between their desires and their actual abilities provides fertile ground for chaos, confusion, and comic misunderstandings as events slowly (and sometimes quickly) spin out of their control.

Seems like a good way to describe the gag behind that sketch. I love how enthusiastic Kermit is at the beginning, and how frustrated he is when he says "Look, the comedian's a bear" for the last time.

To me, that sketch is always funny. I got The Muppet Show Cast Album for my kids, which includes an audio-only version of that sketch. I've listened to it dozens of times. Always funny, for me, at least.

I must admit that I was surprised to learn, from the recent Jim Henson biography by Brian Jay Jones, that this sketch was written by Jerry Juhl right before it was filmed. Frank Oz and Jim Henson read it through once and then did the sketch in one take. According to Juhl, as quoted by Jones, it was the moment when Fozzie really came into his own.

John Seavy over at Fraggmented wrote about the Muppets as part of his storytelling engines series of blog posts. He characterizes the show's engine as the concept that failure is funny:

Looking at the Muppets, you see a group of people united by a) their passion for entertainment and their dram of making people happy through art, and b) their lack of talent at their chosen field. The gap between their desires and their actual abilities provides fertile ground for chaos, confusion, and comic misunderstandings as events slowly (and sometimes quickly) spin out of their control.

Seems like a good way to describe the gag behind that sketch. I love how enthusiastic Kermit is at the beginning, and how frustrated he is when he says "Look, the comedian's a bear" for the last time.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Old Man Coyote

Old Man Coyote and the Buffalo, a Crow story collected in American Indian Trickster Tales, edited by Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz.

Once, when Old Man Coyote saw some buffalo, he wanted to eat them and tried to think of a scheme to do this.

He approached the buffalo and said to them: "You buffalo are the most awkward of all animals--your heads are heavy, your hair legs are chopped off short, and your bellies stick out like a big pot."

The buffalo said to him: "We were made this way."

Old Man Coyote said to them: "I'll tell you what let's do--we will run a race." And all went to a level place with a steep cut bank at the end.

Old Man Coyote said to himself: "I will go and put my robe over the edge of the bank," and turning to the buffalo, he said, "Just as we get to the place where my robe is, we will all shut our eyes and see how far we can go with our eyes closed."

The race was started, and just before getting to the robe, all of the buffalo shut his eyes and jumped over the steep cut bank and were killed; and Old Man Coyote feasted off the dead buffalo.

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

American Tower of Babel

I've been trying to read a story, usually something new, every day.

It's sometimes tough to stick to it, especially when I'm reading

something much longer, but I'm trying to keep it up. I have lots of

collections of legends, folktales, myths, and short stories. When I find

the story worth writing about, I'll include it here.

So today I read a Choctaw story, collected in Stith Thompson's Tales of the North American Indians, page 263. Thompson calls it "The Tower of Babel," but the tower in the story is never named.

In the Choctaw story...well, it's pretty short, and I've got a moment, so here's the whole thing:

Many generations ago Aba, the good spirit above, created many men, all Choctaw, who spoke the language of the Choctaw and understood one another. These came from the bosom of the earth, being formed of yellow clay, and no men had ever lived before them. One day all came together and, looking upward, wondered what the clouds and the blue expanse above might be. They continued to wonder and talk among themselves and at last determined to endeavor to reach the sky. So they brought many rocks and began building a mound that was to have touched the heavens. That night, however, the wind blew strong from above and the rocks fell from the mound. The second morning they again began work on the mound, but as the men slept that night the rocks were again scattered by the winds. Once more, on the third morning, the builders set to their task. But once more, as the men lay near the mound that night, wrapped in slumber, the winds came with so great force that the rocks were hurled down on them.

The men were not killed, but when daylight came and they made their way from beneath the rocks and began to speak to one another, all were astounded as well as alarmed--they spoke various languages and could not understand one another. Some continued thenceforward to speak the original tongue, the language of the Choctaw, and from these sprung the Choctaw tribe. The others, who could not understand this language, began to fight among themselves. Finally, they were separated. The Choctaw remained the original people; the others scattered, some going north, some east, and others west, and formed various tribes. This explains why there are so many tribes throughout the country at the present time.

Thompson gives us the literary source: the Bulletin of the Bureau of American Ethnology, volume xlviii. No Choctaw narrator is named, as is common with old collections of this sort (Thompson's book was originally published in 1929, and the Bulletin was published twenty years before that).

The Babel parallel, or perhaps source, is striking, but for me the differences are more fascinating. Genesis 11 gets into the bricks used, instead of plain old stone, but here rocks are the building materials. I think it's also interesting that the Choctaw teller naturalizes the Choctaw language, and attributes violence to the people who no longer speak it. Also of interest is the different motivations given. In Genesis, the builders of the Tower want to "make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth," if I may quote the folks who put together the New International Version. In contrast, the Choctaw are merely curious. They wonder what's going on up there, with the blue sky and the clouds. Note the folktaleish repetition of three days and three attempts to build the tower, too.

Many myths account for differences between peoples, especially linguistic differences. I've been collecting these sorts of stories for a book project that will probably take the next two or three decades.

I'm no expert on Choctaw folklore. Tom Mould is. He's a folklorist who collected and annotated a book called Choctaw Tales. I remember seeing his dissertation on the shelf among the others at the Indian University Folklore department. It's called Choctaw Prophecy, and my guess is that his book of that name is a revision of that dissertation. Stith Thompson started the Folklore Institute at IU, which later became a full-fledged Folklore Department, and more recently the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology. The department recently moved from a condemnable old fraternity house on 9th and Fess to the recently built and boringly named Classroom Office building on Third Street. I don't know if the bust of Stith Thompson, which sat for so long in the old building, has made the move. Or the dissertations.

So today I read a Choctaw story, collected in Stith Thompson's Tales of the North American Indians, page 263. Thompson calls it "The Tower of Babel," but the tower in the story is never named.

In the Choctaw story...well, it's pretty short, and I've got a moment, so here's the whole thing:

Many generations ago Aba, the good spirit above, created many men, all Choctaw, who spoke the language of the Choctaw and understood one another. These came from the bosom of the earth, being formed of yellow clay, and no men had ever lived before them. One day all came together and, looking upward, wondered what the clouds and the blue expanse above might be. They continued to wonder and talk among themselves and at last determined to endeavor to reach the sky. So they brought many rocks and began building a mound that was to have touched the heavens. That night, however, the wind blew strong from above and the rocks fell from the mound. The second morning they again began work on the mound, but as the men slept that night the rocks were again scattered by the winds. Once more, on the third morning, the builders set to their task. But once more, as the men lay near the mound that night, wrapped in slumber, the winds came with so great force that the rocks were hurled down on them.

The men were not killed, but when daylight came and they made their way from beneath the rocks and began to speak to one another, all were astounded as well as alarmed--they spoke various languages and could not understand one another. Some continued thenceforward to speak the original tongue, the language of the Choctaw, and from these sprung the Choctaw tribe. The others, who could not understand this language, began to fight among themselves. Finally, they were separated. The Choctaw remained the original people; the others scattered, some going north, some east, and others west, and formed various tribes. This explains why there are so many tribes throughout the country at the present time.

Thompson gives us the literary source: the Bulletin of the Bureau of American Ethnology, volume xlviii. No Choctaw narrator is named, as is common with old collections of this sort (Thompson's book was originally published in 1929, and the Bulletin was published twenty years before that).

The Babel parallel, or perhaps source, is striking, but for me the differences are more fascinating. Genesis 11 gets into the bricks used, instead of plain old stone, but here rocks are the building materials. I think it's also interesting that the Choctaw teller naturalizes the Choctaw language, and attributes violence to the people who no longer speak it. Also of interest is the different motivations given. In Genesis, the builders of the Tower want to "make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth," if I may quote the folks who put together the New International Version. In contrast, the Choctaw are merely curious. They wonder what's going on up there, with the blue sky and the clouds. Note the folktaleish repetition of three days and three attempts to build the tower, too.

Many myths account for differences between peoples, especially linguistic differences. I've been collecting these sorts of stories for a book project that will probably take the next two or three decades.

I'm no expert on Choctaw folklore. Tom Mould is. He's a folklorist who collected and annotated a book called Choctaw Tales. I remember seeing his dissertation on the shelf among the others at the Indian University Folklore department. It's called Choctaw Prophecy, and my guess is that his book of that name is a revision of that dissertation. Stith Thompson started the Folklore Institute at IU, which later became a full-fledged Folklore Department, and more recently the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology. The department recently moved from a condemnable old fraternity house on 9th and Fess to the recently built and boringly named Classroom Office building on Third Street. I don't know if the bust of Stith Thompson, which sat for so long in the old building, has made the move. Or the dissertations.

Monday, February 13, 2017

American Alien

I heard Max Landis et al.'s Superman: American Alien was pretty good, so I finally got around to reading it. It came out late last year. Some really good stuff here. When you've got so many artists contributing, the quality will vary, and I liked some issues better than others for precisely that fact. It's a series of essentially stand-alone stories, which I also like. It has its own continuity, but doesn't seem beholden to the DC universe, which I also like.

I don't really have much to say about the stories themselves, though I did notice another example of a recent trend in Superman stories that's worth pointing out: namely, that issues dealing with a young Superman (Superboy?) have to show the tension between Clark and one or both of his parents. In American Alien, this came to the foreground at the end of issue 2 (titled "Hawk"), when Clark and Martha are on the roof talking about Clark's intervention (saving the lives of some folks, mutilating some criminals, getting injured). Clark is worried that his mother sees him as a monster; he's afraid of being rejected. This was also an emotional beat in Geoff Johns and Gary Frank's Superman: Secret Origin. That time it was Clark being worried about his father rejecting him. It's also a more drawn-out theme in early issues of Birthright by Mark Waid and Leinel Francis Yu. This was never part of Jerry and Joe's Superman, to my recollection, nor was it prominent in John Byrne's Man of Steel.

As for movie versions, it's not really present in Superman '78, but it's a big part of Clark's development in Man of Steel.

It fits. Clark's an alien, and in a series whose title foregrounds that quality the tension between an adopted son and his new parents can reflect that otherness. From the examples given above, it's no stretch to say that the relationship between Superman and his adopted parents has become an important aspect of the story. It's key to understanding the current trend in the Superman myth: that Clark Kent is the real identity, and that Superman is an affectation. With the dominance of this interpretation, it's easy to see why the bumbling, mild-mannered Kent has all but vanished (it's worth noting that George Reeves didn't play Kent this way, either; his Kent varied from Superman only in wardrobe).

What conclusions can we draw based on this trend? What does it mean that Superman is not the "real" personality? I think it's a sign that Superman's American-ness is important to people. When Landis's Superman tells Lobo, "I'm from Kansas," (not Krypton) he's embracing a certain patriotism that a lot of people feel is important right now. Kent is American, Kent is human, by choice; Byrne's Superman stories made this an important element of the character, too. At the same time that Superman confirms his American citizenship, Landis shows us that the rest of the world embraces him as well; that fight with Lobo at the end of issue seven is broadcast world-wide.

I don't think there's an intentional response to the story a few years ago in which Superman renounced his American citizenship so that he could be a citizen of the world; this doesn't feel anything like a refutation of that controversial though short and ultimately stand-alone story by David Goyer. But as the international role of the United States, and relationships between countries, change through new administrations and shifting public opinion, it's no surprise that Superman stories would double-down on these themes.

Relationships with parents, with fellow countrymen, with other countries, with aliens...these things are important in Superman stories; they always have been.

I don't really have much to say about the stories themselves, though I did notice another example of a recent trend in Superman stories that's worth pointing out: namely, that issues dealing with a young Superman (Superboy?) have to show the tension between Clark and one or both of his parents. In American Alien, this came to the foreground at the end of issue 2 (titled "Hawk"), when Clark and Martha are on the roof talking about Clark's intervention (saving the lives of some folks, mutilating some criminals, getting injured). Clark is worried that his mother sees him as a monster; he's afraid of being rejected. This was also an emotional beat in Geoff Johns and Gary Frank's Superman: Secret Origin. That time it was Clark being worried about his father rejecting him. It's also a more drawn-out theme in early issues of Birthright by Mark Waid and Leinel Francis Yu. This was never part of Jerry and Joe's Superman, to my recollection, nor was it prominent in John Byrne's Man of Steel.

As for movie versions, it's not really present in Superman '78, but it's a big part of Clark's development in Man of Steel.

It fits. Clark's an alien, and in a series whose title foregrounds that quality the tension between an adopted son and his new parents can reflect that otherness. From the examples given above, it's no stretch to say that the relationship between Superman and his adopted parents has become an important aspect of the story. It's key to understanding the current trend in the Superman myth: that Clark Kent is the real identity, and that Superman is an affectation. With the dominance of this interpretation, it's easy to see why the bumbling, mild-mannered Kent has all but vanished (it's worth noting that George Reeves didn't play Kent this way, either; his Kent varied from Superman only in wardrobe).

What conclusions can we draw based on this trend? What does it mean that Superman is not the "real" personality? I think it's a sign that Superman's American-ness is important to people. When Landis's Superman tells Lobo, "I'm from Kansas," (not Krypton) he's embracing a certain patriotism that a lot of people feel is important right now. Kent is American, Kent is human, by choice; Byrne's Superman stories made this an important element of the character, too. At the same time that Superman confirms his American citizenship, Landis shows us that the rest of the world embraces him as well; that fight with Lobo at the end of issue seven is broadcast world-wide.

I don't think there's an intentional response to the story a few years ago in which Superman renounced his American citizenship so that he could be a citizen of the world; this doesn't feel anything like a refutation of that controversial though short and ultimately stand-alone story by David Goyer. But as the international role of the United States, and relationships between countries, change through new administrations and shifting public opinion, it's no surprise that Superman stories would double-down on these themes.

Relationships with parents, with fellow countrymen, with other countries, with aliens...these things are important in Superman stories; they always have been.

Friday, February 10, 2017

Thursday, February 9, 2017

Childe Roland

For reasons that I won't go into right now, I currently spend a lot

of time thinking about Childe Roland and his sister burd Ellen, who gets

lost in Elfland. I originally encountered Roland, in a vastly different

American form, in Stephen King's Dark Tower novels. I soon learned of

the Robert Browning poem "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came" that had inspired King, and soon after that I

found a copy of the French epic called the Song of Roland. It wasn't

until much later--just about three years ago, I guess--that I found a

folktale called Childe Roland in Katherine Briggs and Ruth Tongue's

Folktales of England. I saw it again in Joseph Jacobs' English Folk and

Fairy Tales, but I found another version in the second volume

of Jacobs' collection. Jacobs got this version from an earlier book,

Jamieson's Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, published in 1814, in

which it's called "Rosmer Haf-Mand." You can read it with the verse here.

The story stars with some verse, which feels very Scottish in its orthography:

Rowland gets to the hill upon which the castle sits. To get inside, he has been told by a hen-wife who now lacks a head, he must go around the hill three times widdershins and repeat "Open, door! open, door! and let me come in." Widdershins means counter-clockwise, or the way opposite the path of the sun, and is the way to walk around a church if you want to get to Elfland or Faerie or whatever magical place suits your fancy.

So Rowland's inside, and he sees a magical castle that's described in some detail, which I won't go into here. He finds burd Ellen sitting on a velvet sofa. They talk of what has happened, but burd Ellen can't say much. When he confesses to great hunger, she keeps quiet but brings him food. Luckily, Rowland remembers Merlin's advice and doesn't eat it. Then comes the King, chanting,

I've been more interested in this story since I came across another reference to it in King Lear not too long ago. In that play, the character Edgar is pretending to be mad, and so he deliberately confuses lines from different fairy tales--"Childe Rowland" and "Jack and the Beanstalk." It's interesting that, two hundred years later (or so) this Scottish version of Childe Rowland makes the same conflation, with the King of Elfland saying the lines of the Giant.

As for the curious word childe...the OED tells us that it's a reference to a highborn youth who is supposed to become a knight. Jacobs in the article linked to above tells us that it refers to an heir. In that sense of the word, he finds evidence that the story dates from an earlier age during which the youngest son was the primary heir to a family's estate. Make of that what you will.

So why is this one of the best stories in the world? I'm a bit biased, since I named one of my sons Roland (which means "famous" in French).

The story stars with some verse, which feels very Scottish in its orthography:

King Arthur's sons o' merry CarlisleSo the sons of King Arthur are kicking a ball around, with their sister burd Ellen watching (burd just means maiden). When Childe Rowland kicks the ball over the church (here spelled "kirk"), Ellen goes to get it. Problem is, she doesn't come back. The boys (there are 3 of them) look for her in vain, finally learning from Merlin (Myrddin Wyldt) that she's been carried away by fairies to the castle of the King of Elfland. Merlin warns them not to pursue her without the proper care and instructions; namely, they have to kill everyone they meet in Elfland and avoid drinking or eating anything while they are there. In true folktale form, the first two brothers (when I tell this story to my kids, I name them Alan and Cuthbert) fail to obey these rules are are trapped in Elfland. Rowland follows, this time obeying the rules. He gets directions to the castle from various herdsmen, all of whom he decapitates with his "good claymore that never struck in vain" (here it seems to be called Excalibur, but that might be an interpolation; in the version in Jacobs' volume 1, it's called a brand--an old word for sword that we got from French, and from which we get the verb brandish).

Were playing at the ba';

And there was their sister Burd Ellen,

I the mids amang them a'.

Rowland gets to the hill upon which the castle sits. To get inside, he has been told by a hen-wife who now lacks a head, he must go around the hill three times widdershins and repeat "Open, door! open, door! and let me come in." Widdershins means counter-clockwise, or the way opposite the path of the sun, and is the way to walk around a church if you want to get to Elfland or Faerie or whatever magical place suits your fancy.

So Rowland's inside, and he sees a magical castle that's described in some detail, which I won't go into here. He finds burd Ellen sitting on a velvet sofa. They talk of what has happened, but burd Ellen can't say much. When he confesses to great hunger, she keeps quiet but brings him food. Luckily, Rowland remembers Merlin's advice and doesn't eat it. Then comes the King, chanting,

"With fi, fi, fo, and fum!There follows a great battle between Rowland and the King. (Harns, by the way, are brains, so harn-pan is head; and there's brand again.) Rowland proves victorious, and convinces the King to free his brothers and his sister. They return home.

I smell the blood of a Christian man!

Be he dead, be he living, wi' my brand

I'll clash his harns frae his harn-pan!

I've been more interested in this story since I came across another reference to it in King Lear not too long ago. In that play, the character Edgar is pretending to be mad, and so he deliberately confuses lines from different fairy tales--"Childe Rowland" and "Jack and the Beanstalk." It's interesting that, two hundred years later (or so) this Scottish version of Childe Rowland makes the same conflation, with the King of Elfland saying the lines of the Giant.

As for the curious word childe...the OED tells us that it's a reference to a highborn youth who is supposed to become a knight. Jacobs in the article linked to above tells us that it refers to an heir. In that sense of the word, he finds evidence that the story dates from an earlier age during which the youngest son was the primary heir to a family's estate. Make of that what you will.

So why is this one of the best stories in the world? I'm a bit biased, since I named one of my sons Roland (which means "famous" in French).

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

Heroism and Superman II

Our thoughts on Superman often parallel our thoughts on the president. This came to the foreground with the widespread references to President Obama in Supermanian terms during the days of his first campaign and early term. And it was no coincidence that Bill Clinton was referred to as Superman when he facilitated the release of two Americans from North Korea a while back.

But I don't want to write about the presidency today--not about broken promises (is a hero someone who always keeps a promise, no matter the consequences?) or exceptionalism or fascism or hope and change. I'm going to write about the Fortress of Solitude.

In Superman '78, a teenage Clark Kent hurls a green crystal into the Arctic ice and witnesses the rise of a place where he can go to be alone, to learn and become the sort of person he wants to be. In the comics, he often does experiments there, and keeps souvenirs and trophies; it's a place of history moreso than anything else. Its purpose is fulfilled when he takes flight for the first time, returning to the world to help it realize its potential. He stops criminals, rescues a cat from a tree, saves Lois Lane.

I see so much rhetoric about both American exceptionalism and isolation, as if keeping the rest of the world out will transform a country into a paradise. I can't help but think of the Fortress of Solitude in that context. Yes, Superman became a hero by isolating himself, but only for a little while--and he wasn't really isolated. He had with him all the learning of his birthplace. He had, in the Fortress, the capacity for change. I worry that isolation (true isolation, as is being proposed; separation from the world itself in an attempt to put America first) will have the opposite effect. Isolation can breed stagnation. After all, if Superman had never left the Fortress, that cat would still be stuck up in the tree.

I'm always wary of any tradition that counsels disengagement from the world.

But I don't want to write about the presidency today--not about broken promises (is a hero someone who always keeps a promise, no matter the consequences?) or exceptionalism or fascism or hope and change. I'm going to write about the Fortress of Solitude.

In Superman '78, a teenage Clark Kent hurls a green crystal into the Arctic ice and witnesses the rise of a place where he can go to be alone, to learn and become the sort of person he wants to be. In the comics, he often does experiments there, and keeps souvenirs and trophies; it's a place of history moreso than anything else. Its purpose is fulfilled when he takes flight for the first time, returning to the world to help it realize its potential. He stops criminals, rescues a cat from a tree, saves Lois Lane.

I see so much rhetoric about both American exceptionalism and isolation, as if keeping the rest of the world out will transform a country into a paradise. I can't help but think of the Fortress of Solitude in that context. Yes, Superman became a hero by isolating himself, but only for a little while--and he wasn't really isolated. He had with him all the learning of his birthplace. He had, in the Fortress, the capacity for change. I worry that isolation (true isolation, as is being proposed; separation from the world itself in an attempt to put America first) will have the opposite effect. Isolation can breed stagnation. After all, if Superman had never left the Fortress, that cat would still be stuck up in the tree.

I'm always wary of any tradition that counsels disengagement from the world.

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

Brian Morris

Brian Morris is a busy guy. He's involved with theater, fiction, comics, and all sorts of stuff. Santastein is of course my favorite of those books he has released so far. What if Frankenstein made a Christmas monster? That's a book for me.

He writes plays, he tweets, he's on facebook (multiply), etc. He's writing comics for a series called Haunting Tales of Bachelor's Grove, which you can fund through its kickstarter. He's often found at conventions for science fiction, fantasy, and comics: here's a profile from the INDYpendent show.

I met Brian in Metropolis, Illinois, in 2009. We talked about Superman a lot, then later about writing, and then more about Superman. There's a chunk of my book devoted to him and his wife, Cookie, and their views of Superman.

In short, he's a good guy, buy his books.

Monday, February 6, 2017

Interesting Superman Stories

Over at The Portalist, Stephen Lovely has a response to the common criticism that Superman's powers make him a dull character. Lovely concludes:

Superman is a serious character with real conflicts. His superpowers aren’t an obstacle to good storytelling any more than most characters’ lack of superpowers are. Superman’s best stories exist in part because writers don’t have an easy crutch to lean on, and that’s an asset, not a weakness. It’s something that, when managed correctly, makes Superman the most rewarding superhero character of all.

I tend to agree.

Superman is a serious character with real conflicts. His superpowers aren’t an obstacle to good storytelling any more than most characters’ lack of superpowers are. Superman’s best stories exist in part because writers don’t have an easy crutch to lean on, and that’s an asset, not a weakness. It’s something that, when managed correctly, makes Superman the most rewarding superhero character of all.

I tend to agree.

Friday, February 3, 2017

Lovecraft Quote

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.H.P. Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu"

Thursday, February 2, 2017

Captured Fairies

A long time ago there were two deadbeats. These men were fond of playing dominoes and singing an odd little tune: "It's my delight, on a shiny night." They got their daily food by poaching rabbits. They did so by taking a ferret and sending it into a rabbit hole while they held a bag over the exit.

One night as they were out a-poaching, the bag was a bit more feisty than usual. As they sang their way through the woods back to their fire pit, the moon came out from behind a cloud. They grew silent, staring at the celestial orb, and suddenly there came a cry from somewhere in the woods: "Dick, wheer art ta?"

To their surprise, something in the bag replied: "In a sack, on a back, Riding up Hoghton Brow."

The man holding the bag dropped it, and the two ran off to hide the rest of the night--hungry and quaking with fear--in a tavern. They told their story to any and all who would give them the time of day, and word spread. From that day onward, the kids in the area became known to follow the deadbeats around town, whispering whenever an opportune moment presented itself, "Dick, wheer art ta?"

I came across this story in James Bowker's Goblin Tales of Lancashire, part of a series called The Illustrated Library of Fairy Tales of All Nations. It's hard to pin down a publication date for for this book, since there's no lawyer page at the front. The copy I got (when the IU Folklore department was selling off its library) is inscribed to somebody called "O Elton" in 1894. It's falling apart. Maybe it's "G Elton." Or "C Elton." It's hard to tell. People must have made letters differently in the nineteenth century.

The author included some comparative notes. For this story, called "The Captured Fairies," Bowker provides some information about the wild hunt, a Teutonic legend in which Odin or some elves or both crash through the world in pursuit of something or other. Apparently the hounds involved in the wild hunt can speak, and when a peasant caught one by accident, much the same thing happened. So there's that.

Because the tale comes from Lancashire, it's got that weird dialect writing. Some stories in the collection are unreadable because of that. Still, lots of good stuff there. It seems to be derived from oral tradition, but Bowker's heavily literized them; for example, here's how he describes their capture of the fairy: "They did not wait long in anxious expectation of an exodus before there was a frantic rush, and after hastily grasping the sacks tightly round the necks, and tempting their missionary from the hole, they crept through the hedgerow, and at a sharp pace started for home." Nothing wrong with that, of course,

So why is this one of the best stories in the world? I think I like it because it's such a silly little thing that actually echoes something profoundly terrifying. The Wild Hunt stems, probably, from terrific storms, during which people could hear howling and whatnot. There was a pretty good issue of Marvel's Thor comic that included a wild hunt, not with Odin. It's that element of disjunction, of the way the story has evolved that makes it great. It's sort of the opposite of the tale of Aurvandil/Earendil in that way.

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)